In financial analysis, valuation is the foundational element for making well-informed choices. Among the many methods available, Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) and Relative Valuation (also called valuation using multiples) stand out for their widespread use across various asset classes and industries.

Over the next few minutes, we’ll break down the differences between these popular methodologies and dissect the benefits and drawbacks of each.

Understanding the Core Concepts

Discounted Cash Flow (DCF)

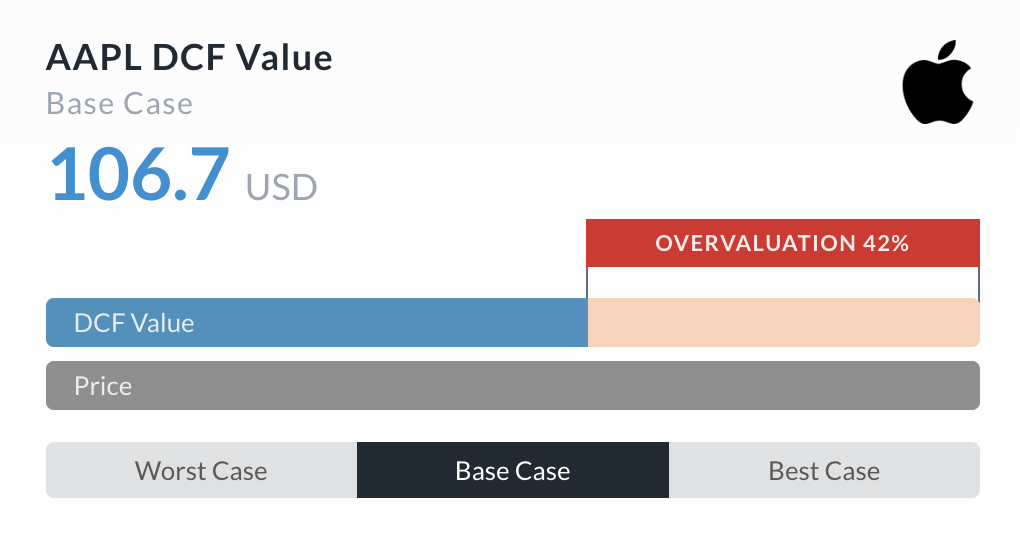

DCF is a valuation method that calculates the present value of an asset’s expected future cash flows. It’s grounded in the principle that the value of an investment is the sum of its future cash flows, discounted back to its present value at a rate that reflects the risk involved.

Notably, DCF models are praised for their rigor and the depth of insight they generate into the intrinsic value of cash-generating assets.

Relative Valuation

Sometimes called Multiples Valuation or Pricing, this method values a company by comparing it to similar ones in its industry or by evaluating its current multiples against historical ones. Typically, common financial metrics, like earnings, sales, or book value, are used for the comparison.

Relative Valuation assumes that similar companies should trade at similar multiples, allowing analysts to easily derive a value for a company based on the market values of its industry peers.

Dissecting the Methodologies

Foundation and Application

DCF valuation is rooted in fundamental financial theory, emphasizing a company’s intrinsic value derived from future cash flows. It’s versatile and applicable to most cash-generating assets.

Relative Valuation, on the other hand, is more pragmatic. It relies on market comparables to gauge value. It’s handy for valuing companies like startups with scarce or unpredictable cash flows.

Regardless, both approaches consider the future performance of the company or asset in their valuation. The critical difference is in how each model addresses these assumptions.

With DCF, assumptions are confronted directly. DCF models explicitly forecast future cash flows and discount them back to their present value.

With Relative Valuation, assumptions are baked in. Ratios are leveraged that implicitly reflect expectations of future growth and probability.

Complexity and Time

DCF models are often criticized for their complexity and the time and detailed information needed to construct them. They demand forecasts of future cash flow and an appropriate discount rate, tasks that involve considerable judgment and can introduce substantial uncertainty. That said, platforms exist, like Alpha Spread, that take on much of the heavy lifting.

Relative Valuation is generally simpler and faster. It leverages readily available market data, making it a popular choice for many. In fact, this strategy is by far the most widely used, followed by DCF, according to a 2019 survey in the Review of Financial Economics.

Subjectivity and Assumptions

While both methods involve assumptions, the DCF approach is particularly sensitive to the inputs for future cash flows and the chosen discount rate. Minor changes in these assumptions can lead to considerable variations in the calculated value.

Relative Valuation, while seemingly straightforward, also carries its own assumptions, particularly the choice of comparable companies and the relevance of the selected multiples to the company being valued.

Market Conditions

The DCF method’s reliance on intrinsic value provides a theoretical anchor less susceptible to market sentiment and volatility. In contrast, Relative Valuation is directly tied to market perceptions and conditions, making it more reactive to changes in investor sentiment and market trends.

Insight and Transparency

DCF models offer deep insights into the drivers of a company’s value, encouraging a thorough analysis of its cash flow prospects and the risks involved. This level of detail and transparency is less inherent in Relative Valuation, which depends more on external market benchmarks than the company’s internal fundamentals.

In some ways, Relative Valuation is the adoption of ‘ignorance is bliss.’ Regardless, at some level, in a broad sense, even Relative Valuation reflects a DCF model, as the multiples used are ultimately derived from the collective market’s expectations of future cash flows and growth prospects.

As noted by prized economist John Burr Williams, Relative Valuation masks the drivers of long-term cash flows. The method uses implicit assumptions rather than tackling them head-on. On the other hand, with a DCF model, you must actively consider these inputs.

Again, while both DCF and Relative Valuation rely on similar assumptions, they differ in approach.

For example, as the risk to future cash flows increases…

- DCF demands a higher discount rate be used to account for the greater risk.

- Alternatively, Relative Valuation demands a lower relative valuation multiple. In other words, it doesn’t directly require a growth rate number in the calculation. Instead, it indirectly implies a growth rate based on the multiple chosen.

Put another way…

- A lower multiple in Relative Valuation models is similar to using a higher discount rate in DCF.

- A higher multiple in Relative Valuation models is similar using a lower discount rate in DCF.

DCF: Pros and Cons

Pros

- Intrinsic Value Focus: DCF models aim to calculate a company’s intrinsic value based on its fundamental earning capacity, independent of current market conditions.

- Future-Oriented: This method emphasizes a company’s future performance, making it a forward-looking valuation approach.

- Flexibility: DCF models can be adjusted to reflect different scenarios and assumptions about a company’s future growth rates, profitability, and capital structure.

- Comprehensive: By requiring detailed forecasts of future cash flows, DCF models encourage a thorough analysis of a company’s business plan, competitive position, and potential for growth.

- Risk Consideration: The discount rate in a DCF model incorporates the risk associated with the investment, providing a way to adjust the valuation for different levels of risk.

Cons

- Complexity: DCF models are mathematically more complex and require more detailed inputs than other valuation methods, making them more time-consuming and onerous.

- Forecasting Challenges: The accuracy of a DCF valuation heavily depends on the quality of future cash flow forecasts, which can be highly uncertain and subjective. For example, DCF can be challenging during the early stages of a company when the potential range of cash flow dispersions is wide.

- Sensitive to Assumptions: DCF valuations are sensitive to assumptions about growth rates, discount rates, and terminal values, which can significantly affect the final valuation.

- Potential for Distored Results: This particular con is more of a user error. Profitable companies with solid growth that rely on intangible assets can end up overstating expenses. This is because intangibles flow directly through the income statement and aren’t reflected as investments on the balance sheet. For example, by default, the benefits of a marketing expense don’t show up on the balance sheet, only as a cost on the income statement. This leads to negative net income despite the company’s success.

However, when addressed correctly, a well-constructed DCF model accounts for these intricacies. In other words, a prudently built DCF model will appropriately categorize future cash flows produced by intangible assets to elicit a more precise valuation and avoid distortion.

- Discount Rate Challenges: Determining the appropriate discount rate can be difficult and contentious, as it involves estimating the cost of capital, which can vary over time and between companies.

- Potential for Bias: The need for numerous assumptions and forecasts in the DCF model can introduce bias, as analysts may have optimistic or pessimistic views that affect their inputs.

Relative Valuation: Pros and Cons

Pros

- Simple and Fast: Multiples are straightforward to calculate and apply, making the valuation process relatively quick and easy to understand.

- Comparability: By comparing companies within the same industry or sector, Relative Valuation allows a quick comparison of a company relative to its peers.

- Market-Based: Since it relies on current market information, the valuation reflects present market conditions and sentiment.

- Useful for Benchmarking: Multiples can benchmark a company against its competitors, helping identify undervalued or overvalued investments.

- Accessibility of Data: The data required for Relative Valuation, such as company financials and market prices, is readily available from financial markets and databases.

Cons

- Reliance on Market Conditions: Multiples are heavily influenced by current market conditions, which can lead to overvaluation or undervaluation if the market is overly optimistic or pessimistic.

- Can be Abused: Users who leverage relative valuation can select assets that bolter their case (i.e., they find highly valued comparables, making their company of focus appear inexpensive).

- Lack of Standardization: Different companies may calculate financial metrics differently, leading to inconsistencies when comparing multiples across companies.

- Ignores Company-Specific Factors: Relative valuation does not consider unique aspects of a company’s operations, growth potential, or risk factors.

- Can Oversimplify Valuation: Relying solely on multiples can oversimplify the valuation process, ignoring the nuances of a company’s financial health, future prospects, and the broader economic context.

- Blind to its Bubble: By ignoring intrinsic value, Relative valuation may be comparing two overvalued assets to begin with. In other words, it may reveal that company A is undervalued relative to B, but it says nothing about the value of either company versus the broader market.

So, Which One is Better?

While DCF may be more complex and arduous, it can reflect a more candid and precise approach than Relative Valuation.

At the same time, DCF doesn’t always work. It requires cash-generating assets, so it’s unusable when valuing investments like artwork. It’s also ineffective for businesses in the early stages of development.

With Relative Valuation, investors can rapidly glean insight into a particular stock, but not so with the more complex inputs needed for DCF.

Still, on balance, honest discounted cash valuations can prove immensely insightful. The market can only ignore true value for so long. Eventually, intrinsic value will reel in the market price like a “magnetic force,” to borrow the term from a 2021 paper by Michael J. Mauboussin and Dan Callahan.

Ultimately, both methodologies have their merits and drawbacks. Appraising each one’s benefits and limitations is critical to harness their power. It’s also important to acknowledge that both approaches, at some level, are based on common assumptions. The key distinction lies in how these assumptions are formulated.

After all, Wall Street’s best investors and traders are open to leveraging both, with the clear understanding that neither is perfect.

Jesse Oberoi

I’ve held the CFA charter since 2017.

With a career spanning over 15 years in the finance industry, I’ve been fortunate to amass a diverse set of experiences spanning multiple domains.

I’ve managed multi-billion dollar tactical asset allocation calls as a Portfolio Operations Manager.

I’ve been responsible for a group of flagship, multi-asset class funds exceeding $4B in AUM as a Product Manager.